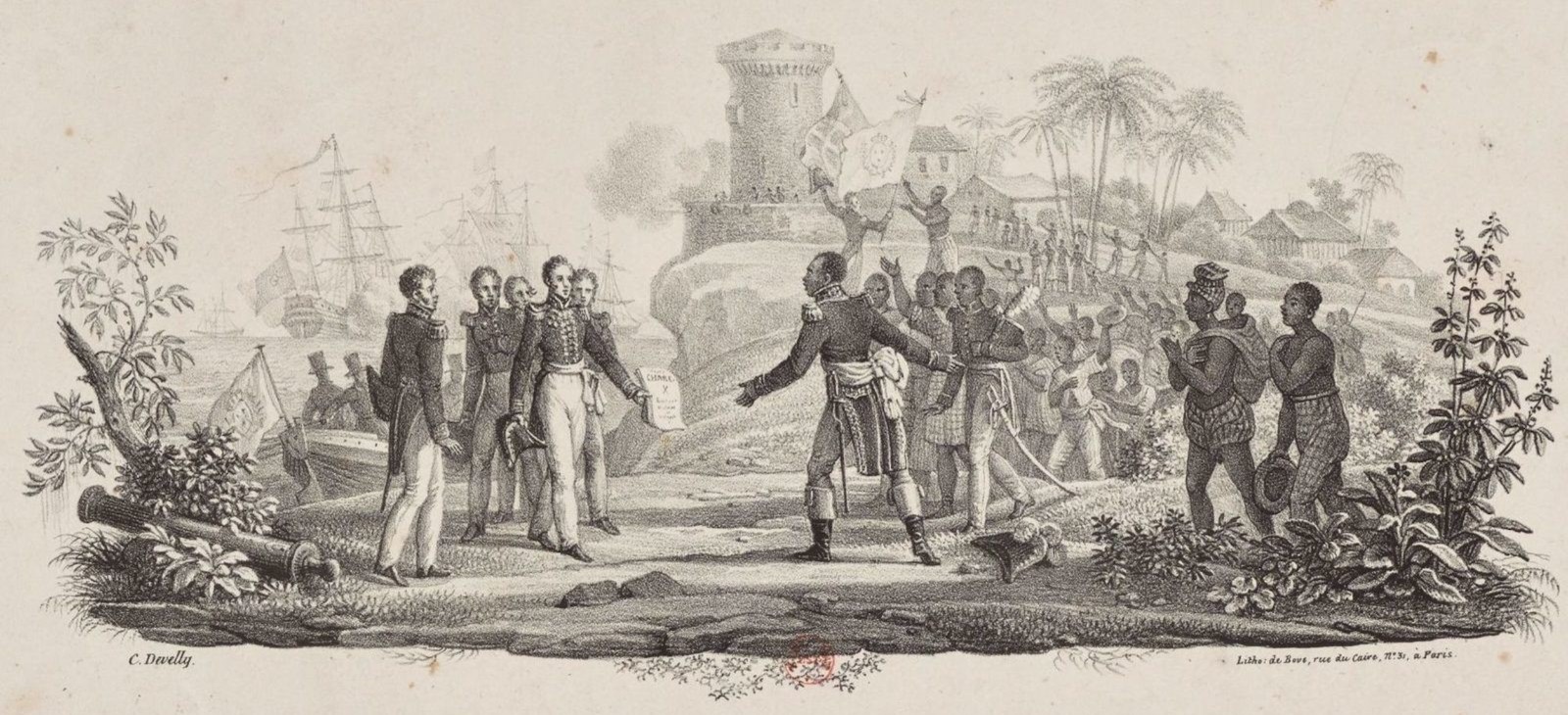

In exactly one year's time, it will be two hundred years since Baron de Mackau, emissary of the King of France, transmitted the Ordinance of Charles X to the then President of Haiti, Jean-Pierre Boyer, on April 17, 1825.

As Haitians, we have a duty to remember, and we believe that revisiting this event, which marked the course of our country's history, is an essential part of our duty to ourselves and to future generations. Let us first consider the facts of history.

The loss for France of its richest colony at the end of the turbulent 18th century, the failure of the expedition to re-establish slavery, the victory of the indigenous army over Napoleon's troops, the declaration of independence by the new state - the first and only one made up of former black slaves and a few freedmen - the sequence of these events in a relatively short space of time was intolerable for France and for all the great powers of Europe still involved in the slave trade and in slavery.

For 21 years, France attempted reconquest by seeking alliances with England, Spain and the United States, and as a last resort, it chose to impose the ordinance in which it is written: “We concede under these conditions... to the present inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue, the full and complete independence of their government”.

Haiti is not named.

Two clauses to remember, which will weigh heavily on the future of our young republic: firstly, customs duties levied in ports, either on ships or on goods, both on entry and exit, will be reduced by half for French flags. Secondly, “... The present inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue will pay to the Caisse générale des dépôts et consignations de France, in five equal terms, from year to year, the first due on December 31, 1825, the sum of one hundred and fifty million francs, intended to compensate the former colonists who will claim an indemnity.”

On July 3, 1825, 14 warships armed with 528 cannons arrived in Port-au-Prince harbor. On board was Baron de Mackau, commissioned by King Charles X to impose France's terms, by force if necessary... Under the threat of a naval blockade and military intervention, on July 8, 1825, President Boyer agreed to pay the indemnity. To pay it, Haiti would have to take out a loan with French banks. The whole package - the indemnity and the loan - is commonly referred to as the double debt of independence.

Over the coming months, we will be looking back at the key historical events that preceded and followed the signing of the ordinance by the government of the day and its successors, over the course of Haiti's long 19th century, and at the analyses offered by historians from Haiti and elsewhere.[1]

[1] We would like to salute Florence Alexis, the Curator, and the Scientific Council of the excellent exhibition held at the beginning of 2024 at the Panthéon in Paris, entitled "Oser la liberté" ("Daring Freedom"). Charles X's ordinance was on display, along with a wealth of documentation on "Figures in the fight against slavery". We also salute the excellent work of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de l'Esclavage - https://memoire-esclavage.org - , co-organizer of this exhibition.

For morre information :

Books :

- Jean-François Brière. Haïti et la France, 1804-1848: le rêve brisé. Éditions Karthala, 2008.

- Marcel Dorigny, Jean Marie Théodat, Gusti-Klara Gaillard, Jean Claude Bruffaerts. Haïti-France Les chaînes de la dette – Le rapport Mackau (1825). Éditions Hémisphères, 2021, 201 p.

Texts available online :

- Gusti-Klara Gaillard-Pourchet. La dette de l’indépendance d’Haïti. L’esclave comme unité de compte (1794-1922)

https://heritage.bnf.fr/france-ameriques/fr/dette-independance-haiti-article

- Gusti-Klara Gaillard-Pourchet. Haïti-France. Permanences, évolutions et incidences d’une pratique de relations inégales au XIXe siècle

https://journals.openedition.org/lrf/2844?lang=de

- Beauvois, Frédérique. L'indemnité de Saint-Domingue: « Dette d'indépendance » ou « rançon de l'esclavage » ? French Colonial History, vol. 10, 2009, p. 109-124. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/fch.0.0021.

https://web.archive.org/web/20190430033100id_/https://muse.jhu.edu/article/266552/pdf

- Beauvois, Frédérique. Monnayer l'incalculable ? L'indemnité de Saint‑Domingue, entre approximations et bricolage, Revue historique, vol. 655, no. 3, 2010, pp. 609-636.

https://www.cairn.info/revue-historique-2010-3-page-609.htm

- Oosterlinck, Kim and Panizza, Ugo and Weidemaier, Mark and Gulati, Mitu, A debt of dishonor. (April 30, 2022). Boston University Law Review, vol. 102:1247

https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2022/05/OOSTERLINCK-PANIZZA-WEIDEMAIER-GULATI.pdf

Press and online videos :

- LA RANÇON – THE RANSOM – RANSON AN

par Lazaro Gamio, Constant Méheut, Catherine Porter, Selam Gebrekidan, Allison McCann et Matt Apuzzo, The New York Times, 20 Mai 2022

French Version :

- Les Milliards Envolés

https://www.nytimes.com/fr/interactive/2022/05/20/world/americas/haiti-france-dette-reparations.html

- À la racine des malheurs d’Haïti: des réparations aux esclavagistes

https://www.nytimes.com/fr/2022/05/20/world/haiti-france-dette-reparations.html

Creole version :

- Milya Ayiti pèdi yo

- Rasin mizè Ayiti: Reparasyon yo bay Mèt esklav yo

https://www.nytimes.com/ht/2022/05/20/world/ayiti-lafrans-esklavaj-etazini.html

English version :

- Haiti’s Lost Billions

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/05/20/world/americas/enslaved-haiti-debt-timeline.html

- The Root of Haiti’s Misery: Reparations to Enslavers

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/world/americas/haiti-history-colonized-france.html

In Spanish :

- La 'doble deuda' con la que Francia ahogó a Haití en el siglo XIX

Silvia Nieto, ABC Internacional, 05/06/2022

VIDEOS

- “La dette de l'indépendance haïtienne, un sujet tabou en France”. Haïti Inter, 6 juin 2023

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v_0oqN5hl1o&list=PL6XuTdsJrZQ-9RvBNOZtDJJvkrJ0Pcx-a&index=6

- Thomas Piketty : l'économie en Haïti. Emission "Éco d’ici Éco d’ailleurs, RFI, 19 octobre 2019

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XQcjp_lRbU&list=PL6XuTdsJrZQ-9RvBNOZtDJJvkrJ0Pcx-a&index=5

- Why did Haiti agree to pay reparations to France after the Haitian Revolution ? Choices programs. 6 oct. 2021, The Haitian Revolution. Anthony Bogues, Brown University.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ea2PfhCtp2Q&list=PL6XuTdsJrZQ-9RvBNOZtDJJvkrJ0Pcx-a&index=11

- La multimillonaria indemnización que Haití le pagó a Francia por su independencia

//www.youtube.com/@BBCMundo">BBC News Mundo, 22 mars 2024

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJ-dHYlRj-0&list=PL6XuTdsJrZQ-9RvBNOZtDJJvkrJ0Pcx-a&index=14

À l’initiative de Haiti Development Institute, FOKAL et Ayiti Demen, la 5ème conférence des Bailleurs pour Haïti a été réalisée à Washington du 12 au 14 juin 2023. Cet événement a mobilisé des représentants de plusieurs organisations basées en Haïti et à l’étranger. Pour ouvrir la conférence, la Présidente de la FOKAL, Mme Michèle D. Pierre-Louis a prononcé un discours à la fois captivant et inspirant sur « Comment la philanthropie peut-elle contribuer à l’avancement d’Haïti ? Elle a aussi adressé la situation actuelle d’Haïti et le rôle que doivent jouer les différents acteurs, tant nationaux qu’internationaux, pour redresser cette situation.

Lisez ci-dessous l'intégralité du discours.

The Fifth Haiti Funders Conference Keynote Speech

Washington, D. C. Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis

June 12-14, 2023

I want to thank the Haiti Development Institute and its Executive Director Pierre Noel for inviting me to offer the keynote for this Funders Conference and I hope my opening remarks will meet the expectations of the organizers by touching on a few important issues that can lead to honest and productive debates and conclusions today and tomorrow.

I want to thank the Haiti Development Institute and its Executive Director Pierre Noel for inviting me to offer the keynote for this Funders Conference and I hope my opening remarks will meet the expectations of the organizers by touching on a few important issues that can lead to honest and productive debates and conclusions today and tomorrow.

I was asked to consider how best to meet this moment and support interventions that will bolster and usher in systemic change. I will start by questioning “this moment”.

We all know how life-threatening today’s situation in Haiti is. Political deadlock, high insecurity due to gang violence, environmental fragility, unchecked migration, brain drain, economic stagnation, food insecurity, and a collapse of State institutions that has been a long time coming through decades of missed opportunities and imposed international policies that tragically weakened local capacities. We Haitians have our own issues to confront but isn’t it the whole world that seems to be in crisis? And aren’t we constantly experiencing the devastating effects of manmade disasters caused by the developed world, with limited means to protect ourselves? For example, the expanded US production of easily accessible guns and assault weapons that are just as easily smuggled to Haiti with catastrophic results. When we look at what is going on in so many countries worldwide, we realize how long and strenuous is the path to transforming in a sustained way the living conditions of our own targeted marginalized population, children and youth, smallholder farmers, women, artists and artisans, etc.

Today, politics seem to no longer mean caring for the affairs of the city, the search for the common good and upholding public interest. In many countries, the disconnect between the power structure and its constituencies is abyssal and what we too often hear about is corruption, lies, mismanagement of funds, endless wars, disregard of constitutional and legal rights, distortion of the check and balance system, alternate realities, denial of history, all serious issues that dominate what we learn daily of governments and of the highest institutions. And some believe that this is the way it should be.

At home, when we see government officials, past and present being sanctioned for crimes of corruption, massacres, gang relations, and yet participating in international and national events.

At the social level, the thirst for endless profits from legal and not so legal businesses has widened the divide of our communities’ social fabric. A situation French philosopher Jacques Rancière describes as “la fracture entre les gens de biens et les gens de rien ». The fracture between the rich and the poor as a factor of increasing inequalities. The World Inequality Report 2022 informs that “The world’s richest 10 per cent own more than three quarters of global wealth”.

The social categories already historically marginalized pay the highest price. The youth have lost confidence in the future, a large majority remains unemployed and seeks alternative ways to give sense to a life that seems meaningless: drugs, criminality, jail, or migration under dangerous conditions.

Yes, we live in a world of violence, unsafe for all. Even scientific progress creates major disruptions in our planetary system by contribution to pollution, health issues and climate change. The crisis has penetrated our minds and threaten our human dignity. We are indeed grappling with a major crisis of values.

All this describes the somber side of our reality that does affect our morale and the way we conduct our activities. Paradoxically, there is another side in “this moment”, that of hard work, resistance, solidarity, empathy, a world of care, learning, community engagement, good causes, radical joy and hope. That is where philanthropy plays a major role if we are faithful to its etymological meaning: philos love, anthropos, humankind.

At FOKAL I have called the communities where positive change occurs despite adverse conditions, “pockets of hope”. They are our success stories that need to be told and upheld. Communities and organizations in all geographic departments that struggle hard to keep their dignity and their humanity.

But can we say that these interventions bolster and usher in systemic change, the other component of the question I am supposed to address today?

I will begin by reviewing the major channels for transfers of funds towards Haiti and then try to analyze if they address the causes rather than the symptoms of complex social and political situation, which is what systemic change means.

I will start briefly with the international donors and raise a few questions about the multilateral and bilateral institutions. Their primary partner remains the government, but they sometimes reserve some funding for civil society organizations. I was inspired by a presentation made by economist Daniel Dorsainvil, former Minister of Economy and Finance in the GOH, at a conference held by the Haiti Think Tank in June 2022.

Why have the efforts of multilateral banks and donor governments had so little success in Haiti?

What changes are needed in the design and implementation of programs and projects to improve results?

Why are the conditionalities covering a wide range of sectors supposed to be attained in short terms?

Why is so much money wasted repeatedly year after year while Haiti continues to be the labeled “the poorest country in the hemisphere” ?

I do not have clear answers to those questions, but I know that at the same time,

the lack of palpable results obtained in Haiti is said to cause “Haiti fatigue” within the donor community. On the receiving end of the aid, those very disappointments generate a “Haitian fatigue” with international donors and their local decision maker relays that stems from prolonged political instability, increasing poverty, bad economic prospects and lost opportunities.

Dorsainvil made a comprehensive and comparative study on where international aid may have failed in the case of Haiti.

I share with you a few of his findings:

- “The aid policy designed for Haiti is different from the one that has been conceived for other Least Developed Countries (LDC) in that it has a more humanitarian component than in other countries with similar poverty profiles and needs.

- Resources actually spent are far less than the amounts that are committed. This affects the economic sectors more than the social sectors, and there have not been enough Official Development Assistance (ODA) resources allocated to productive sectors.

He identifies six factors that explain the relative ineffectiveness of foreign aid in generating better outcomes in Haiti. They include:

- An issue of scale: the effective aid package is generally too little with respect to the challenges

- Absence of clearly stated (quantified) medium term economic objectives with well formulated strategies and action plans

- The humanitarian trap

- Aid resources are leveraged, and there is insuffcient coordination, alignment, stakeholder consultation

- Failure to improve GOH’s credibility and legitimacy in the provision of public services

- Shocks, natural disasters, political and social upheavals (assassination of a President), health pandemics, high price of gas, etc.”

It is as if Haiti is incapable of creating economic, social, intellectual, symbolic wealth, and only deserves humanitarian aid.

A second sector that transfers funds is the diaspora. I will not get into the complex network of organizations that support families and communities in Haiti. I will just make a note about the remittances that amounted to close to 3.1 billion dollars in 2022.

The study made for CEPAL, Mexico in 2019 by Fritz Duroseau and Edwige Jean on behalf of the Central Bank of Haiti reveals interesting findings. I share some data with you:

- Remittances count for about 32% of the GDP and represent 10 times the international aid.

- 72% come from the US; 7% from Chile; 4.4% from Canada; 2.7% from the DR and 2.3% from Brazil.

- 45% of remmittances are between 100-500 USD; 16.4% between 500-1000 USD; and 23% 1000 USD and above.

- Most remittances are small amounts received on a monthly basis. They finance basic consumption expenditures (food, education, health, rent). The most frequent profile of senders is the blue collar worker,

- Remittances positively impact the beneficiairies, reduce poverty and improve the human development indicators: from 1960 to 1980 to 2017, life expectancy at birth grew from 41 to 50 to 64 years, while the GDP per capita moved from 70 to 243 to 768 USD during the same period. GDP per capita at the time of the study was 900 USD; in 2021 it was 1829,59 USD and in 2022, 1283,05 as per the World Bank.

- Remittances are also an instrument of risk mitigation in difficult times (hurricanes, droughts, funerals and other catastrophes)

- Some remittances concern land purchase, small business investment owned by migrant workers.

However, while being the main source of foreing currency inflows, remittances also have their negative impact. Haiti is a net importer of goods, thus remittances finance imports of non-productive goods. The flows came with new consumptions habits that make the economy very vulnerable to external price shocks as it has become more dependant on imported goods and services.

And to echo Duroseau and Jean’s study, Daniel Dorsainvil adds:

“It has been documented that remittances that are sent to Haiti help finance consumption (over 80%)[1] rather than investment. Also, much of the country’s consumption (food and other consumer goods) is made up of imported goods because domestic productive capacity is low, and remittance flows may not be as relevant for rapid growth as other resources since it is re-exported to a large measure and therefore does not have a large impact on capital build-up due to import leakage”.

These short reviews shows nonetheless that the interventions from both sectors, the international donors and the remittances seem to yield mixed results at the very best.

The measures of deregulation and structural adjustments imposed by the international donors in the 1990s have dismantled the traditional economic fabric and turned Haiti into a net importer of the most necessary goods that it used to produce. Both the rural areas and the cities are on survival mode.

There is a need to act on both the cities and the rural areas. Different financial sources should serve to support the municipalities, define the rules, the limits, the zoning, the authorizations. Develop useful infrastructures that can create jobs while protecting the environment, natural resources and national heritage. Partnering with universities in Haiti and abroad can help develop new adapted technologies that can increase productivity, and most of all alleviate the weight of rural manpower which is today too expensive for the smallholder farmers.

I will now consider philanthropy.

Interventions of institutions like FOKAL and so many others in this room are made possible through philanthropy, thanks to dedicated donors who believe in our commitment on the ground and share their savoir-faire and experience while providing the financial support that can sustain our strategies. I want to take this opportunity to express how grateful we are to all the donors that fall in that category.

Philanthropy it is said stands on five pillars: inclusion, transparency, empowerment, collaboration, and celebration.

If today our convening is an occasion to celebrate, it is also a time to question, to express our concerns about our own practices regarding inclusion, transparency, empowerment, and most of all collaboration.

Our position in the philanthropic field is very specific. We depend on funds provided by donors, based on shared ethical values, and agreed upon methodologies and procedures, and we distribute those funds to communities, organizations, and social actors to support underfunded causes that government, and often international donors and foreign NGOs do not address.

We are working with people and dealing with systems implying multiple stakeholders. There are fundamental questions to be raised:

- Do we share among ourselves (staff, donor, targeted population)

the same definition of concepts such as sustainable development, democracy, the rule of law, human rights, gender justice, racial equity, systemic change, etc.?

- How sure are we that our work is geared towards emancipation and does not reinforce existing inequalities and marginalization?

- How do we balance our budget that accounts equitably between our programs funding and the institution’s reproductive needs?

- How measurable is our action? Can we admit failures and draw from lessons learned?

- What is our position vis-à-vis the Government and public institutions, public services?

Debating these questions may help us give meaning to the pillars of inclusion, transparency, and empowerment, but what about collaboration?

This is probably the most difficult objective to attain and seems to be also a condition to achieve systemic change. At the national level, the absence of coordination from the State is a major factor of waste, duplication, even of corruption. But that is not the only problem. In philanthropy, our existence depends on external funding from donors. We must constantly prove ourselves to be deserving, through competition, access to what has become a market. Each local institution establishes itself in its own field, a specific geographic area, with its own “beneficiaries” and see no interest in collaborating with other institutions or organizations who are often funded by the same donor.

It is true that some effort is being made towards more collaboration, but still a lot needs to be done, not only among us, but also with other stakeholders whose role is important: universities, private sector, local government, and whenever possible the public sector.

Philanthropy can help to network, to sustain social enterprises (impact investment), environmental initiatives, marketing and transforming of goods and services. But it should also be understood as a learning process that respects local knowledge and savoir-faire, grasps the complexities of the survival strategies, avoids the bureaucratic entanglements, and questions accepted notions such as the ideology of participation, fashionable gimmicks, victimization etc.

My limited experience has taught me how much working with local actors and their respective municipalities can be an effective model. Communities then learn about the mechanism of local governance and can mobilize for additional resources while being watchful of corruption and clientelism. Intersecting experiences are being conducted at Gros-Morne, Verrettes, Anse-à-Pitres, Cavaillon, Saint-Louis du Sud, Camperrin, Barradères, to name a few, without much publicity, engaging the communities in civic work, reforestation, value-added crops, animal farming, small enterprises. New techniques and technologies are introduced based on scientific experiments. They change behaviors while creating more cohesion among the participants.

Here we are talking about long term interventions that allow us to analyze and update existing data, select the priorities, and spend time on the ground to seize the complexity of each terrain while engaging with the communities. The country’s chaotic situation is certainly a handicap, but we must anticipate, weigh what is possible and take risks. There is nothing wrong with impact and measurement, but when that is the only focus and they are deployed at the expense of meaning and understanding, something fundamental is lost.

Systemic change implies time, innovation, sustainability, adaptation to changing conditions, thinking critically, proximity and scaling up. It also builds on mobilizing educated young people, to create a new generation of women and men that can project their future in the country because they foresee a positive horizon, rather than be tempted by Humanitarian parole or another mirage of the sort.

We have done a lot, but there is still so much more to be done. And as once said by a great man “Yes we can!” Wi nou kapab!

Thank you.

[1] Orozco, M. - Understanding the remittance economy in Haiti, Inter-American Dialogue, a paper commissioned by the World Bank, March 2006.

Haiti is now in an unsustainable situation. Change must happen in all sectors. We believe that Philanthropy can play a pivotal role in Haiti’s resurgence with strategic investments now.

Haiti is now in an unsustainable situation. Change must happen in all sectors. We believe that Philanthropy can play a pivotal role in Haiti’s resurgence with strategic investments now.

There ARE solutions and inspiring examples of partners working with communities to outpace poverty, inspire youth and prepare for a better tomorrow.

If you are a philanthropic institution, donor, impact investor or social entrepreneur seeking the best way to support Haitian communities to leverage their assets and pursue paths to prosperity, then,

This conference is for you.

In partnership with Haiti Development Institute and Ayiti Demen, FOKAL is pleased to invite you to join us on June 12-14, 2023, in Washington, D.C.

Links for registration and accommodations are at www.haitidevelopmentforum.org or here : https://www.haitidevelopmentforum.org/funders-conference

If you are interested in sponsorship opportunities or wish to get involved, please reach out to Liz Fischelis at

We count on your attendance!

"I've always thought of them as a big family. A group of people who care about helping young people get their careers off the ground."

"I've always thought of them as a big family. A group of people who care about helping young people get their careers off the ground."

We invite you to watch this excerpt from an interview with Gessica Geneus, one of FOKAL’s former grantees. Gessica is a living testimony to FOKAL’s commitment to youth and communities through education and art. FOKAL is proud to have been a part of her journey, that took her to the red carpet of the Cannes film Festival in 2021 for her fiction film Freda. Her accomplishments strengthen our beliefs in the capacity of Haitian youth and the will of women to empower themselves.

FOKAL has chosen to target populations that are most apt to become agents for change in the Haitian society: children and youth, civil society and grassroots associations, and historically marginalized sectors such as smallholder farmers and women. The organization also promotes the structures necessary for the establishment of a just and durable democratic society, based on individual and collective autonomy and responsibility.

FOKAL is a co-honoree of the Zayed 2022 award.

Click here to watch the video.

Ayiti Diaspora Collaborative (ADC) is launching a survey to gain better insights and understanding of the various Haitian communities across the United States. They call all people of Haitian descent living in the United States to be part of a historic movement and share their thoughts in the ADC Nationwide Survey.

Ayiti Diaspora Collaborative (ADC) is launching a survey to gain better insights and understanding of the various Haitian communities across the United States. They call all people of Haitian descent living in the United States to be part of a historic movement and share their thoughts in the ADC Nationwide Survey.

The results of the survey will be used to craft a roadmap to amplify the voice of our vibrant diaspora and increase its influence.

The survey, designed in partnership with FIU’s Jorge M. Pérez Metropolitan Center, is part of a broader research initiative undertaken by ADC in collaboration with the W.K Kellogg Foundation to harness the Haitian American collective power.

ADC (Ayiti Diaspora Collaborative) is a collaborative of renowned organizations based in the US and in Haiti that reflects our community and that has been advocating on behalf of our people for over forty years.

ADC Members include the Haitian American Foundation for Democracy, Sant La, Avanse Ansanm, Ayiti Community Trust, FOKAL, Haitian American Professionals Coalition, Haitian American Voters Empowerment Coalition, Haitian Bridge Alliance, Haitian Ladies Network, Haiti Renewal Alliance, Quisqueya University, and Replenish 509.

Please clink on the link below to get more information about the survey.

December 12, 1972 – January 12, 2010 – January 12, 2023

December 12, 1972 – January 12, 2010 – January 12, 2023

A series of two special online programs to commemorate the twelfth anniversary of the January 12, 2010 earthquake and the fiftieth anniversary of the first boatload of Haitian refugees that arrived on the Florida coast

Part two

OUR COMMUNITIES

BROADCAST JANUARY 12, 2023

4 H 53 PM

On January 12, 2010, an earthquake of magnitude 7.1 devastated our country, killing hundreds of thousands. Since this tragedy, every year FOKAL commemorates the earthquake of January 12, 2010.

On December 12, 1972, the first boatload of Haitian refugees fleeing the persecution and extreme conditions of the U.S.-backed Duvalier regime arrived on the Florida coast. Since December 12, 2022, and throughout 2023, the Haitian diaspora in the United States commemorates this first arrival, which marks the beginning of 50 years of crossings, tragedies but also resistance, solidarity, and new departures for more than one million Haitian immigrants currently living in the United States.

On the occasion of this double commemoration, FOKAL will broadcast on January 12, 2023, at 4:53 pm a special program, entitled "Our Communities". This program is the second part of the program entitled "A Fifty-Year Journey". Like the first one, this program alternates songs and texts to punctuate a conversation between personalities living in Haiti and in the diaspora, in the presence of an audience of student members of debate clubs and artists.

This second program evokes the struggles and the path taken by all Haitians emigrated to Florida to become a strong community. It evokes among other things the problems that our communities face, the sometimes complex relationships between Haitians and their families in the diaspora, the problems of youth here and there... Its primary objective is to establish a permanent dialogue between Haiti and its diaspora, to open avenues to work differently, to seek solutions together, and to carry a word of hope.

Edwidge Danticat, writer, Santra Denis, director of the Avanse Ansanm association in Miami, Eliézer Guérismé, artistic director of the Festival En Lisant, Gepsie Metellus, director of SANT LA, Haiti Neighborhood Center in Miami, Lorraine Mangonès, director of FOKAL and Michèle Pierre-Louis, president of FOKAL, participate in this conversation recorded on the virtual platform ZOOM.

Texts and songs are interpreted by Staloff Tropfort and Miracson Saint-val for the texts, and for the songs, by the choristers of KORAL FOKAL directed by Daphné Ménard, as well as by the singers Néhémie Bastien, ans the singers Charline Jean Gilles, Vanessa Jeudi, accompanied by the musicians Josué Alexis at the piano, David Casséus at the bass, Emmanuel Jean Baptiste at the drums, Francisco Sardau Lafrance at the percussion instruments, and Kerby Jimmy Toussaint at the guitar.

The program was produced by Michèle Lemoine, from an original idea by Lorraine Mangonès, in collaboration with Gary Lubin for the artistic direction, Réginald Louissaint Junior for the direction of the photography and the editing of the songs, and Laurence Magloire, Mwèm TV, for the recording and editing of the conversation.

The show can be followed on FOKAL's Facebook and Instagram pages and Youtube channel and will be relayed simultaneously on the Facebook pages of many partners.

December 12, 1972 - December 12, 2022

December 12, 1972 - December 12, 2022

A series of two special online programs to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the first boatload of Haitian refugees that arrived on the Florida coast and the twelfth anniversary of the January 12, 2010 earthquake.

Part one

CROSSINGS

BROADCAST DECEMBER 12, 2022, 6 H PM

On December 12, 1972, fifty years ago, the first boatload of Haitian refugees fleeing the persecution and extreme conditions of the U.S.-backed Duvalier regime arrived on the Florida coast.

On December 12, 2022, the Haitian diaspora in the United States commemorates this first arrival, which marks the beginning of 50 years of crossings, tragedies, but also of resistance and solidarities, and new departures for more than one million Haitian immigrants currently living in the United States, and will be an opportunity to look back on 50 years of Haitian migration, migration policy and US involvement in Haiti:

- By paying tribute to the many victims and to those left behind;

- by looking back at the Duvalier dictatorship, chronic political instability and tragic events that have punctuated the history of our country for fifty years;

- by tracing the history of U.S. migration policies that, from 1972 to the present, systematically and specifically subjected Haitians to racist, illegal and inhumane treatment, and by analyzing how U.S. policy in Haiti has shaped the emigration of Haitians to the U.S, as well the situation in Haiti, contributing to the complex process that led to the current collapse;

- by recalling the struggle of Haitians and of activists who supported them for the respect of their rights, the hard work of Haitian organizations and their allies in the United States to defend and assist migrants;

- By establishing the foundations for an essential dialogue between Haiti and its diaspora.

FOKAL is contributing to this commemoration through its Media and Arts and Culture programs. On this occasion, the Foundation is producing two special programs that will be broadcast online. These programs mix songs, recitations, and discussions/reflections in small groups in the presence of an audience of student members of debate clubs and artists.

The first program will air on December 12, 2022 at 6:00 pm. It attempts to look at the periods of the great waves of Haitian migration from 1972 to the present from a global perspective, linking them to the history of Haiti and to U.S. policy towards the country: it emphasizes the policy of illegal and systematic detention and other humiliations, vexations, and persecutions targeting Haitians in particular.

Edwidge Danticat, writer, Guerline Jozef, director of the Haiti Bridge Alliance, Gepsie Metellus, director of SANT LA - Haiti Neighborhood Center in Miami, Lorraine Mangonès, director of FOKAL and Michèle Pierre-Louis, president of the Foundation, participate in a discussion recorded on the virtual platform ZOOM.

This discussion, conceived as a shared History telling, is punctuated by texts and songs interpreted by Edwidge Danticat, Gaëlle-Bien Aimé and Eliézer Guérismé for the texts, Néhémie Bastien, Charline Jean Gilles, Vanessa Jeudi, for the songs, accompanied by musicians Josué Alexis on piano, David Casséus on bass, Emmanuel Jean Baptiste on drums, Francisco Sardau Lafrance on percussions, Kerby Jimmy Toussaint on guitar.

The program was directed by Michèle Lemoine, from an original idea by Lorraine Mangonès, in collaboration with Gary Lubin for the artistic direction, Réginald Louissaint Junior for the direction of the photography and the editing of the songs, and Laurence Magloire, Mwèm TV, for the recording and editing of the discussion.

Discours de Mme Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis à l'ouverture du symposium de "Haitian Ladies Network"

Nous publions en intégralité le discours de Mme Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis à l'ouverture du symposium de "Haitian Ladies Network", le samedi 8 octobre 2022, à Washington D. C.

We publish the full speech of Mrs. Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis at the opening of the symposium of "Haitian Ladies Network", Saturday, October 8, 2022, in Washington D. C.

Haitian Ladies Network

Washington D. C.

October 8th, 2022

I am honored to be here today and want to express my heartfelt thanks to the Haitian Ladies Network for having invited me to their 2022 annual symposium. A special event indeed!

I am honored to be here today and want to express my heartfelt thanks to the Haitian Ladies Network for having invited me to their 2022 annual symposium. A special event indeed!

As I was pondering on what I was going to say today, I asked myself: why do hundreds of women from such diverse horizons convene here annually in Washington D. C. for three days? What brings them together? To me there is only one answer: Haiti. Yes, Ayiti. Whether you were born in Haiti, like me – and in my case in Jérémie, the most beautiful part of the country! – whether you were born in the United States, in the Caribbean, or any other place in the world, one symbolic power unites us here, Ayiti. The first country in the world to affirm that Black Lives Matter!

Eighty thousand women who have this in common can bring change if not to the world (and that remains to be seen) but indeed to Haiti!

And yet, it is so difficult today to talk about Haiti, the complexity of its current situation and what the population is constantly going through. I live in Haiti, I work there, I teach there, I have family there and so many people I care deeply about. Every day, I dread to hear that people I know have been kidnapped, raped, wounded, or even murdered. Every day. And I will not list here for you the long list of friends, relatives and companions who have fallen victims of this violence. You have all heard of the dismantling of the State and of all public institution, of massive corruption and of the criminalization of political personnel, of high unemployment, and inflation, “lavi chè”, of what has become a generalized humanitarian crisis. The gangsterization of the whole country is a new devastating phenomenon. And one that can only have developed with the support of traffickers that supply weapons and ammunitions from a place where such weapons are manufactured, a place all profits return to.

In the meantime, we are distracted by gang leaders giving press conferences, interviews to local and foreign medias. Who post videos on social media, giving to their vociferations and violent threats the pretense of political discourse, while the most vulnerable they claim to incarnate are their first and most numerous victims, those most cruelly treated under the impervious gaze of our officials and of their international allies.

This is the unbearable situation we confront every day. Not a fiction. Our reality.

Nonetheless, Haitians have throughout history taught the world lessons in Resistance. Yes, we resist. It is from that mindset and praxis of Resistance that we share, communicate, learn, exchange, build, express solidarity, create and hope.

Today, despite the catastrophic situation of Haiti, I chose to convey to you the spirit of resistance that guides three major sectors of Haitian society: the women, the peasants (also designated as smallholder farmers), and the artists. These are sectors that need to be connected, encouraged, and supported by the diaspora and particularly by a large network like yours. As are no doubt other sectors not described here, but I chose those as I work with them. I have chosen a somewhat historical angle to take us away from the tragic chaos of today, an invitation to turn our gaze on possibilities for the future and on solidarities to be built today in lucid urgency.

Haitian Women

In Haiti’s demographics, women count for 52% of the population. Haitian scholar Mireille Neptune Anglade appropriately referred to women as “the other half of development”, the title of her 1997 book. Her important analysis is based on her historical research on the role of Haitian women in the productive sectors (mostly agriculture), and on why Haiti has the highest rate of women single-parent families in the region. As she noted, for over two centuries, men were absent: slavery, marronnage, war of Independence, defense of territorial integrity, migration to sugar plantations in Cuba & the Dominican Republic, civil wars, resistance to US occupation, exile, transitioning in hardship to the diaspora… Such absence created a total imbalance of roles, putting women in a situation of unfair over-responsibility. Any social or political reflection on change should start by examining the place and role of Haitian women in society.

The Haitian women’s right movement is one of the oldest and most exemplary in the Latin America and Caribbean region. In Haiti, it is one of the rare sectors of civil society that has historically advocated for structural and systemic change in favor of women but also in favor of the most vulnerable sectors of society.

In Haiti, the struggle for women's rights started in the 1930's when a group of educated women, the Women’s League, took to the streets of Port-au-Prince to claim the rights of all women to be full-fledged citizens capable of participating in the country's political and social life. Another important focus for them was the public denunciation of brutal sexual violence committed by US marines of the then occupying forces against girls and women.

Their advocacy campaign, while public opinion did not particularly favor the emancipation of women, obtained in 1944 a presidential constitutional amendment allowing women to be candidates for election at the municipal level and for the lower house of Parliament, not for the Senate or the Presidency. That major step was marred with contradiction as women could be elected but still did not have the right to vote.

On the international and regional level, the League gave active support to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of December 10, 1948, and to Haiti’s adhesion to the newly created United Nations. They mobilized for the ratification of the InterAmerican Convention of May 2, 1948, giving political rights to women; and the UN Convention of June 20th 1951 on equal pay for equal work.

In 1957 Haitian women obtained the right to vote and participated massively in the election. However, when Duvalier proclaimed himself president for life in 1963, he affirmed his suspicion and hostility to all civil society organizations that were not subordinated to the dictatorship. Until the fall of the Duvalier regime in 1986, the women’s movement remained dormant except in the diaspora.

On April 3rd, 1986, two months after Duvalier’s departure, women from all social sectors organized a massive demonstration asking for a new constitution that guaranteed women’s rights to vote, and to participate in the democratic process the country was engaged in. April 3rd became National Women’s Day in Haiti and is celebrated every year by women’s organizations throughout the country.

The post dictatorship women’s and feminists’ organizations recognized the pioneers’ work and took it to the next level with more specific advocacy regarding women’s rights: respect and support to different types of families; legal status of children born out of wedlock; recognition of rape as a crime, status of domestic workers; reproductive rights; equity vis-à-vis peasant women in the rural areas whose work remains invisible.

Their mobilization for the creation of a Ministry of Women’s Rights was successful and the Ministry was created in 1994. For the past 25 years, the women and feminists’ organizations imposed two major items on the national agenda: the struggle against gender-based violence and women’s political participation.

In 1997, Haitian feminists’ organizations held a symbolic international tribunal on gender-based violence and the recommendations served to negotiate with Parliament the necessary changes in laws discriminating against women. In 2005 the government of Haiti published a decree recognizing the different forms of sexual aggressions and the appropriate sanctions. Rape was finally treated as a crime. Medical doctors received administrative circulars from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of women’s rights asking them to deliver the medical certificate that is an essential document in trials against perpetrators.

The January 12, 2010, devastating earthquake hit the movement hard. Among the victims, several well-known feminist leaders among the most prominent. Relaunching the movement became arduous even more so because of two additional factors: the massive invasion of international NGOs coming with big money that chose to create circumstantial short-lived groups of women while bypassing the local organizations; and the equally massive invasion of fundamentalist religious sects targeting primarily women’s rights and Vodou culture.

Today a new generation of young feminists is emerging with their own vision and actions, but they owe their actual conditions to the engagement, courage, and teachings of the previous generations of feminists. As the struggle for women’s rights and against gender-based violence continues, they need to be supported and encouraged. I want to acknowledge the presence here of Danièle Magloire,

feminist and human rights activist, and a pillar of FOKAL’s Board of directors. Her exemplary commitment and courage in the fight for women’s rights and gender justice make us proud. Her name is associated with all the gains in this ongoing fight. Thank you Danièle.

Smallholder Farmers

As I turn to deep rural Haiti and to the Haitian peasants, the smallholder farmers, I will read a quote that I frequently use because it clearly describes their historical drive to create a new way of living based on mutual respect and solidarity.

In her book Taking Haiti, Military Occupation & the Culture of Imperialism, 1915-1940, American scholar Mary Renda writes: “Haitian peasants had struggled to establish a peasant economy and to resist forces urging them toward plantation wage labor. Picking coffee and growing food for themselves and for the market in their own garden plots afforded greater levels of control over their lives than plantation agriculture would allow… They worked body and soul for economic independence.”

In the wake of our independence, the rural communities imagined a new political and social order capable of offering them the space needed to reconstruct their lives as communities who had suffered, and vowed to never again suffer, the racism, the terror, and the constant violence of the plantation system. They wanted to build their own identity in their struggle for equality. Land ownership was the basis of economic freedom but also a matter of dignity and power.

The notion of honor was (and remains) a priority in their struggle: those who introduce themselves with honor should be greeted with respect! This remained true throughout the 19th century and a good part of the 20th century. This is the cultural source of the spiritual strength, resistance, imagination, and creativity for all of us. This is Ayiti.

Today we are contemplating the devastating effects of two concomitant factors:

- First, the gradual dismantling of the peasant economy begun in 1986, begun when the Haitian Ministry of Economy and Finance embraced the deregulation of our imports prescribed by the IMF,

and followed more decisively in 1994 when President Aristide returned from exile with US military support and deregulation was consecrated. How can a Haitian peasant, still working with the 18th century hoe, and with practically no support, compete with the highly subsided US farmer from Biloxi, Mississippi or Ouachita, Arkansas? Our rice production that used to feed 80% of the population is now reduced to barely 20%. The local production of rice used to provide for close to half a million families and now to only 130 000 families, mobilizing 30 000 temporary workers, 90% in the Artibonite valley. In 1986 the tax on imported rice was at 50%, in 1987 at 35% and in 1995 it went down to 3%. Today Haiti is the second largest importer of US rice after Mexico, before Japan and Canada. These policies destroyed both the urban and the rural areas and inexorably reduced public revenues.

- The second factor is the fast-growing demographic in the country. The population has doubled in 30 years, from 6 million when Duvalier was ousted in 1986 to an estimate of 12 million today.

Our already overcrowded cities, including the Capital, with no real productive economy, no appropriate urban infrastructures, no adequate housing, schools, health facilities, have become a breeding ground for gang violence.

While migrations seemed to be an escape for many whether for economic or political reasons, those who stayed had to suffer the outcome of measures adopted without questioning their medium and long-term effects.

It is a matter of JUSTICE to invest in the rural areas with the smallholder farmers, with women heads of families that also cultivate land and carried for centuries the burden of going to the markets to sell their produce and to keep alive what remains of the rural economy. Justice for the population whose back breaking coffee production paid the indemnity, the debt and the double debt contracted by force in 1825 to compensate the colonial slave owners, while maintaining those vital populations in the margins.

Our own experience at FOKAL, though limited, is a continuous transformative process of learning, listening, and sharing that works both ways. Our relations of proximity on the ground are now sadly limited by the gangs’ control of the main roads, but we keep in touch by all other means, and we support their resistance. The fight against food insecurity, the promotion of local production, the preservation of our biodiversity and the protection of the environment can gain momentum only through long term investments, and respect for the leadership of smallholder farmers organizations, not through humanitarian aid.

The Arts

Finally, let me touch on the artistic world. Creating incredible works of art in adverse conditions, in precariousness, in “peyi lòk”, in defiance of dictatorship and of more covert forms of repression, that is what the artists and artisans of Haiti, women and men, constantly demonstrate in all fields: visual arts, dance, music, literature, iron works, cinema, theatre, photojournalism, traditional crafts…

As an example, every year since 2003, the Festival de Théâtre 4 Chemins takes place toward the end of the year. I remember in 2004, I was a member of the selection committee and the city of Gonaïves was totally flooded by hurricane Jane.

Most inhabitants had lost everything, and we were heartbroken by the distress. A question was raised: should we cancel the festival? After debate and arguments, we decided to go ahead. And I was asked to explain why at the launching event. The space was packed. I don’t know what inspired me, I just said: “the committee has decided to go along with the festival. This festival will be dedicated to the people of Gonaïves as a testimony of our solidarity.” There was a moment of silence, then a standing ovation. I was relieved but I also understood what that meant. Creating in times of disaster demands respect and a continuing engagement from the artists as well as from the public.

Since then, every year the festival takes place, often in the midst of social unrest or natural disasters. Most of the events happen in the streets, in improvised spaces, markets and public squares, there is no standard performance space in Haiti.

FOKAL ran the festival for 10 years before rightfully transferring the leadership to an association of artists highly conscious of the role theater plays in raising awareness on vital civic issues. We are extremely proud of this demonstration of the sector’s capacity to take charge of the festival.

Artistic and artisan communities are numerous, particularly in the wider Port au Prince area, but also in many other areas of the country. They are rooted throughout the country in the struggles for survival that are the fabric of Haitian life. In l’Artibonite, in the South, in Port au Prince, traditional and modern creation, crafts and arts cohabit and collaborate. Of note among many is the community of iron artisans and artists established in the village of Noailles, in Croix-des-Bouquets. Established since the 1940’s, they are an extraordinary example of transgenerational transmission rooted in popular culture. They have been attacked by gangs on several occasions with deadly casualties but continue to create inspirational artistic works with the support, among others, of FOKAL and of Fondation Afrikamerika. Their creations could be seen in a magnificent exhibit last June and they still work miracles to remain connected to regional markets in the Caribbean and in the US.

A lot could also be said about dance and music, and about our writers whose literary works are often awarded internationally, but that would be the subject of an entire conference. They are messengers of the spirit of Ayiti, the troublemaker and disrupter of oppressive orders, the artists themselves incarnating the ultimate individual defiance of all controlling forces.

At last, I want to honor Le Centre d’art, another beacon of resistance and creativity. As the chair of the Board, I thank HLN for giving us the opportunity to make our work known and to raise desperately needed funds to preserve the oldest institution dedicated to Haitian artists with an incredible track record going back to 1944, and today vibrant, audacious and younger than ever. Most of our prominent artists recognize the role Le Centre d’art played, and still plays, in their artistic journey.

When we resumed our activities after the peak of Covid-19, in January 2021, Le Centre d’art held a major exhibit, titled RÈL, of prominent artists from Bel Air, and from Grand Rue who were totally decapitalized by the pandemic but also by the senseless violence inflicted on their communities by gangs and police alike.

This year, in January, in collaboration with Le Musée d’art haïtien, the work of 3 generations of women artists were exposed. This past June, the exhibit Archipelago showed the work of 9 women Caribbean artists (Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, St Vincent, Jamaica, Dominican Republic, Barbados) in an exchange program sponsored by UNESCO. In July, 8 winners of a call for proposals launched in collaboration with the Swiss Embassy in Haiti and supporting creative artists exhibited their works. All of these powerful celebratory moments occurred in Port au Prince under siege by incomprehensible violence. Indeed, we resist.

All these events receive hundreds of visitors and take place at Maison Dufort, a gingerbread house restored by FOKAL after the 2010 quake. The fundraising campaign launched by the Centre d’art aims at restoring its own historical landmark house recently acquired thanks to the generosity of one of its main sponsors Fondation Daniel et Nina Carasso of France.

Please visit the stand, learn about Le Centre d’art, and donate.

I started my speech by saying that what bring us together today and is at the heart of this symposium is Ayiti. Not a phantasmatic Haiti made of illusory dreams, not a faraway third of an island crippled with the avatars of geopolitics, globalization and collapsed governance. What I invoke with you is the real spirit of Ayiti, that of freedom, of solidarity among and with those who suffer, of mutual understanding, of honest commitment. The spirit of resistance igniting the soul of our women, smallholder farmers and artists. The spirit that can enlighten our path and, as said by the great poet Aimé Césaire, give us “the strength to look at tomorrow”. La force de regarder demain. Fòs pou nou gade demen !

Kenbe fèm!

Thank you! Mèsi anpil !

Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis,

October 8, 2022

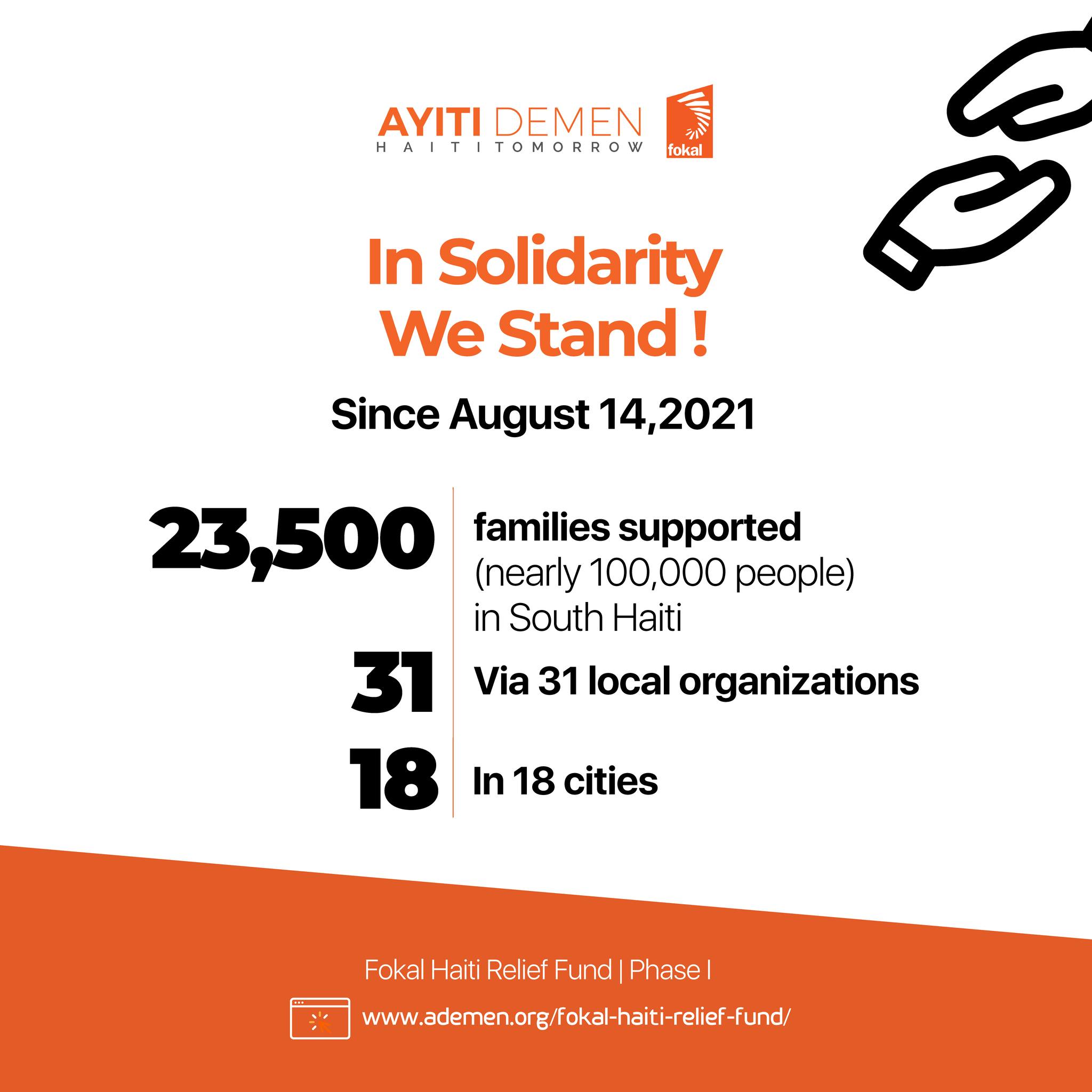

On August 14, 2021, a devastating earthquake shook the southern region of Haiti, leaving more than 2,200 people, and 12,200 wounded and destroying homes, livestock, and crops. Then came the tropical storm Grace a few days later, aggravating the devastation and suffering.

On August 14, 2021, a devastating earthquake shook the southern region of Haiti, leaving more than 2,200 people, and 12,200 wounded and destroying homes, livestock, and crops. Then came the tropical storm Grace a few days later, aggravating the devastation and suffering.

Ayiti Demen and the Foundation for Knowledge and Liberty (FOKAL) responded swiftly by issuing a call for help to provide emergency aid and long-term recovery support to the population. Nearly 3,340 compassionate individuals joined this initiative by making financial donations. As a result, about 23,500 families –an estimated 100,000 people–received food, drinking water, medical supplies, building materials to repair roofs, and cash to purchase seeds and school supplies.

We are truly thankful for your generosity! You can continue to support us on our website: www.ademen.org

We invite you to watch this video to discover the various interventions carried out in the South to help many families affected by the earthquake.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzyQ2MrBFaU

In 1998, to pay tribute to those who at the end of the 18th century fought against colonization, slavery and racism on the territory that is now Haiti, UNESCO declared August 23 the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

In 1998, to pay tribute to those who at the end of the 18th century fought against colonization, slavery and racism on the territory that is now Haiti, UNESCO declared August 23 the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

On the night of August 22-23, 1791, a general slave insurrection broke out in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. This conflagration opened the way to an unprecedented war which ended, in November 1803, with the battle of Vertières that brought the victory of the Indigenous Army over the troops of the Napoleonic army who had come to re-establish slavery abolished since 1793. Giving back to this land its original Taïno name of Haiti announced a deep desire for profound change at the time of the proclamation of Independence on January 1st 1804.

Independence was unacceptable in a world based on slavery and colonialism. The price to pay was heavy for the young republic, and it was even heavier for the inhabitants of the countryside, anonymous heroes and heroines of this war, for whom the notions of freedom, equality, honor and dignity were to find their full meaning in the radical rejection of the old order.

This long history of dehumanization lasted four centuries and still profoundly marks the world today. Over time, the documentation on the slave trade and on slavery has become more and more extensive. Social scientists, historians, geographers, archaeologists and philosophers have delved into it to understand, analyze, compare and branch out the components of this vast global enterprise that was the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trade and the enslavement of millions of captives taken from the African continent. The world of creation, from the visual arts to writing, music and dance, has also opened up important insights into the traces left by these crimes, but also into the power of refusal and the strength of emancipatory struggles.

In these dreadful times, when our country is experiencing an extreme level of destructive violence, we must reflect on what that night of August 22-23, 1791 held in promise for a new world, and try to rediscover the deep meaning of these ideas of freedom and equality that are at the very foundation of what Haiti is.

- Zayed Award for Human Fraternity announces Jordan’s King Abdullah II and Queen Rania, and Haitian humanitarian organization FOKAL as 2022 honorees

- FOKAL Haiti Relief : Support for organizations in the Southern Peninsula of Haiti

- BREATHE. REMEMBER. RESIST.

- A visual campaign on sexual consent

- Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis honored with WPL Trailblazer Award 2020

- Rêver d'arc-en-ciel, a new children's magazine

- Live here, Inhabit the world

- Ayiti Demen replaces Friends of Fokal, subscribe to the new newsletter!

- Carline Fermont, a volunteer in Martissant for 9 years

- Matthew; a year later. A letter from the Camp-Perrin debate club